Neurosurgery billing is not for the faint of heart. It sits at the intersection of complex anatomy, high-risk procedures, strict payer scrutiny, and some of the highest RVUs in modern medicine. One wrong CPT code, one missed modifier, or one weak operative note can easily cost a practice thousands of dollars on a single case.

Unlike primary care or routine outpatient specialties, neurosurgery claims are almost always reviewed closely. Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial payers know these procedures carry high reimbursement. Because of that, they expect airtight documentation and precise coding every single time.

In this guide, I will walk you through neurosurgery CPT codes in detail. We will cover procedure categories, global surgery rules, modifier usage, documentation expectations, payer policies, reimbursement trends, and common billing traps. This is not surface-level theory. This is how neurosurgery medical billing works in the real world.

Scope of Neurosurgery CPT Coding

Neurosurgery CPT codes primarily fall within the 61000–64999 and 63000–69990 ranges. These sections cover procedures involving the brain, spine, spinal cord, peripheral nerves, and related structures. Unlike office-based specialties, most neurosurgery codes represent technically demanding operative services performed in hospitals or ambulatory surgery centers.

What makes neurosurgery coding different is the layered service structure. A single case may involve exposure, decompression, instrumentation, fusion, microscopy, and postoperative management. Each element has its own CPT rules, bundling edits, and modifier requirements.

According to CMS utilization data, spine procedures alone account for over 65% of neurosurgical billing volume, with lumbar and cervical surgeries leading the way. Cranial procedures, while fewer in number, carry significantly higher RVUs and audit risk.

To bill correctly, you must understand not only the code description but also what is included, what is excluded, and when separate reporting is allowed.

Cranial Neurosurgery CPT Codes Explained

Cranial procedures involve surgery on the skull, brain, meninges, and intracranial structures. These are among the highest-value CPT codes in medicine, and they require exceptional documentation.

Common cranial neurosurgery CPT codes include craniotomy and craniectomy procedures, such as 61510 for tumor resection or 61304 for intracranial decompression. These codes typically include surgical access, exposure, closure, and standard intraoperative care.

One critical billing rule many practices overlook is that approach and closure are bundled. You cannot separately bill for scalp incision, bone flap creation, or standard wound closure unless a distinct, medically necessary service is documented and allowed by payer policy.

Microsurgical techniques are often used in cranial cases. CPT 69990 may be reported when an operating microscope is used, provided the primary procedure does not already include microscopy. Many cranial CPT codes already bundle microscopic work, making 69990 inappropriate in those cases.

Payers frequently deny cranial claims when operative notes fail to clearly state laterality, lesion location, depth, and surgical intent. Words matter here. “Mass removal” is vague. “Gross total resection of left frontal lobe meningioma via craniotomy” is billable language.

Spine Surgery CPT Codes and Their Billing Complexity

Spine surgery is where most neurosurgery practices generate consistent revenue, and also where most denials occur. CPT spine codes are divided by region: cervical, thoracic, and lumbar. Each area has distinct coding rules that must be followed carefully.

For example, lumbar discectomy codes such as 63030 apply to a single interspace and a single level. If the surgeon performs the procedure at an additional level, 63035 may apply, but only under specific circumstances and payer policies.

Fusion procedures are even more complex. Codes like 22612, 22630, and 22633 represent different fusion techniques and anatomical regions. These codes do not include instrumentation. If hardware is placed, additional CPT codes such as 22840–22847 may apply, depending on the type of instrumentation used.

A common mistake is overreporting instrumentation codes. Medicare, in particular, closely reviews whether instrumentation was medically necessary or simply supportive. The operative report must clearly state why hardware placement was required and how it contributed to spinal stability.

Decompression, Laminectomy, and Discectomy Coding

Decompression procedures relieve pressure on neural structures and are frequently performed alongside other spine surgeries. CPT codes like 63047 for lumbar laminectomy are often misunderstood.

These codes include the decompression of neural elements at a specific level. If multiple levels are decompressed, add-on codes such as 63048 may be reported. However, these add-on codes must be supported by explicit documentation showing separate levels treated.

Discectomy codes focus on the removal of disc material. Surgeons often dictate “disc decompression” without specifying whether nucleus pulposus removal occurred. That wording matters. Payers may downcode or deny if the operative note lacks clarity.

Bundling edits also comes into play here. Decompression may be bundled with fusion procedures unless performed at a different level or for a separate diagnosis. This is where modifier -59 or -XS becomes essential, but only when properly justified.

Peripheral Nerve Surgery CPT Codes

Peripheral nerve procedures involve carpal tunnel release, ulnar nerve transposition, nerve repair, and neuroplasty. These procedures fall within CPT ranges 64700–64999.

Although these codes appear simpler, they still carry billing pitfalls. For instance, carpal tunnel release CPT 64721 includes exploration and release of the transverse carpal ligament. Additional billing for neurolysis or exploration is not allowed unless a separate nerve is treated.

Laterality is crucial in peripheral nerve billing. Modifiers -RT and -LT must be used correctly. Missing laterality is among the top five reasons for denial of peripheral nerve claims across commercial payers.

Despite lower RVUs than cranial or spine cases, peripheral nerve procedures often generate steady outpatient revenue. Clean claims and strong documentation here significantly improve overall cash flow.

Modifier Use in Neurosurgery Billing

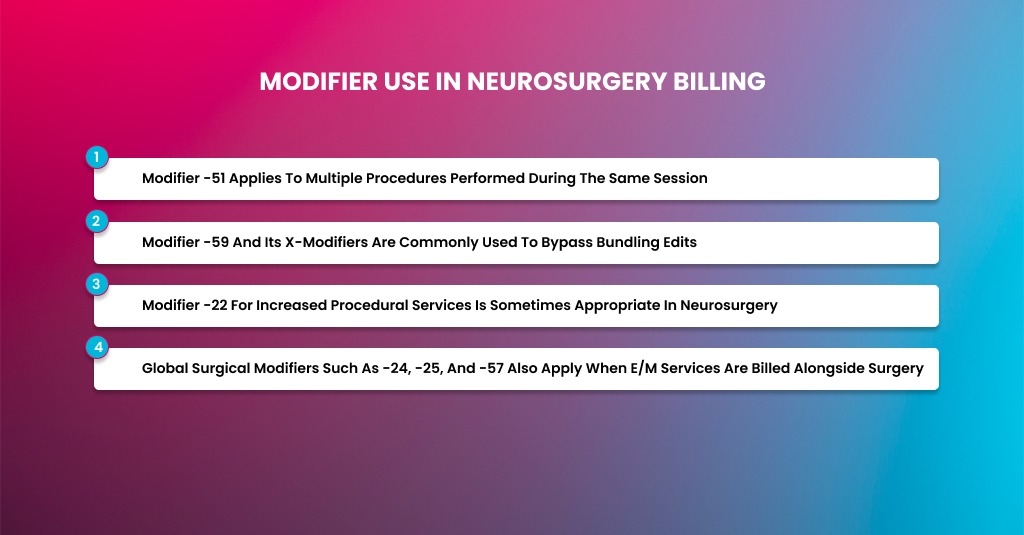

Modifiers can make or break a neurosurgery claim. Because procedures are complex and often combined, correct modifier use is essential.

- Modifier -51 applies to multiple procedures performed during the same session, but many payers automatically use it. Manual misuse can reduce reimbursement unnecessarily.

- Modifier -59 and its X-modifiers are commonly used to bypass bundling edits. However, these modifiers are heavily audited. Documentation must clearly show that procedures were distinct, separate, and medically necessary.

- Modifier -22 for increased procedural services is sometimes appropriate in neurosurgery due to anatomical complexity or unusual circumstances. However, it requires a detailed operative note and often a separate cover letter. Without that, claims will be denied outright.

- Global surgical modifiers such as -24, -25, and -57 also apply when E/M services are billed alongside surgery. Neurosurgeons often underbill legitimate E/M services due to fear of audits, leaving money on the table.

Global Period Rules and Postoperative Billing

Most neurosurgery CPT codes carry a 90-day global period. This includes routine postoperative visits, postoperative pain management, and standard follow-up care.

Billing E/M services during the global period requires careful documentation. Modifier -24 applies only when the visit is unrelated to the original surgery. Modifier -25 applies to significant, separately identifiable same-day E/M services.

Medicare data shows that improper global period billing is responsible for nearly 18% of neurosurgery audit findings, making this an area practices must monitor closely.

Documentation Requirements That Payers Expect

Neurosurgery documentation must tell a complete story. Payers expect precise diagnoses, imaging correlation, failed conservative treatment, and detailed operative reports.

Operative notes should describe anatomical levels, laterality, pathology, techniques used, and intraoperative findings. Templates help, but copy-paste errors raise red flags.

Preauthorization is another critical factor. Many spine and cranial procedures require prior approval. Billing without it almost guarantees denial, regardless of medical necessity.

Reimbursements for Neurosurgery CPT Codes

Neurosurgery reimbursement is not universal. The same CPT code can pay very differently depending on whether the payer is Medicare or a commercial insurance plan. Understanding these differences is not optional. It directly impacts cash flow, contract negotiations, and even surgical decision-making.

Many neurosurgery practices struggle because they apply one billing mindset to all payers. That approach does not work. Medicare follows rigid national rules. Commercial payers follow contracts, policies, and internal algorithms. Let’s break this down in a practical, real-world way.

Medicare Payments for Neurosurgery Services

Medicare reimbursement for neurosurgery is driven by the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS). Every CPT code is assigned relative value units (RVUs). These RVUs are split into three parts: physician work, practice expense, and malpractice.

Once RVUs are totaled, they are multiplied by the annual Medicare conversion factor to determine payment. This means Medicare payments are standardized nationwide, with only small geographic adjustments.

For neurosurgery, this creates predictability. A lumbar laminectomy or a craniotomy will pay the same base rate across the country, assuming the same CPT code and modifiers. However, predictability does not mean generosity. Over the past several years, CMS has gradually reduced or rebalanced RVUs for specific spine procedures, especially fusions.

Medicare typically pays 20–40% less than well-negotiated commercial contracts for the same neurosurgery CPT codes. Yet, Medicare remains attractive because payments are consistent and relatively timely when claims are clean.

Medicare Coverage Rules and Medical Necessity

Medicare does not rely heavily on prior authorizations for neurosurgery, but that does not mean it is lenient. Instead, Medicare enforces coverage through Local Coverage Determinations (LCDs) and National Coverage Determinations (NCDs).

These policies define when a procedure is considered medically necessary. For example, many spine procedures require documentation of failed conservative treatment, correlating imaging, and specific neurological findings.

If a neurosurgery claim does not meet LCD criteria, Medicare may deny or recoup payment after the fact. This is why documentation quality is critical. Medicare audits are retrospective, and recoupments can happen months or even years later.

Medicare Global Period and Modifier Expectations

Medicare strictly enforces global surgery rules. Most neurosurgery procedures carry a 90-day global period. Postoperative visits related to the surgery are not separately reimbursed.

Medicare closely monitors modifier usage, especially -24, -25, -57, and -59. Overuse or misuse is a common trigger for audits. In neurosurgery, Medicare expects clear, separate documentation when these modifiers are applied.

Unlike many commercial plans, Medicare does not negotiate. There is no flexibility once rates and rules are set.

Commercial Insurance Plans for Neurosurgery

Commercial payers operate under contracted fee schedules rather than a single national standard. Each contract may pay a different percentage of Medicare or a fixed dollar amount per CPT code.

Some commercial plans pay 120–180% of Medicare for neurosurgery services, especially for high-demand specialists. Others pay only slightly above Medicare, particularly in highly competitive markets.

This variability makes commercial reimbursement less predictable but often more lucrative. It also means billing teams must understand each contract in detail to spot underpayments.

How to Bill Neurosurgery CPT Codes

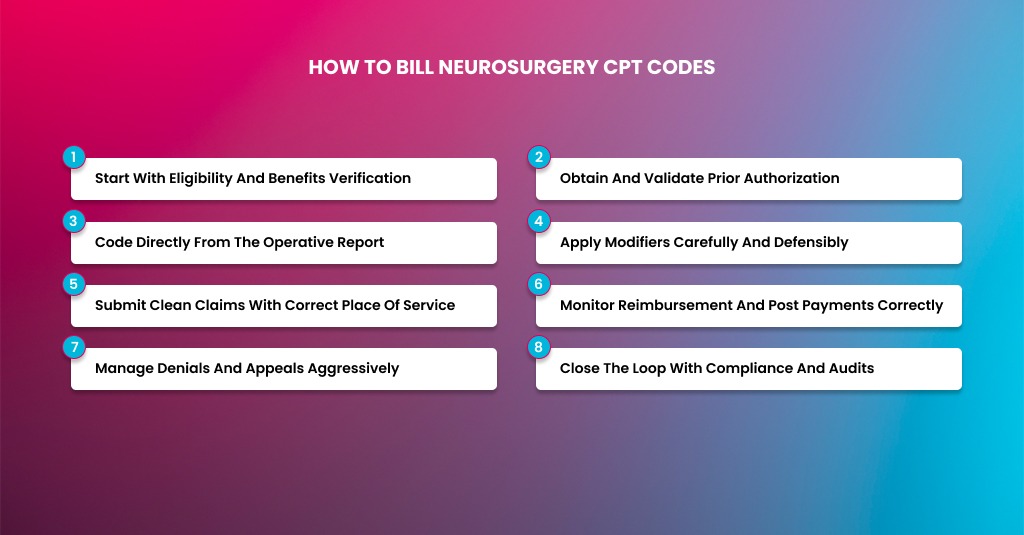

Billing neurosurgery services is a process, not a single action. Many practices lose revenue by focusing only on CPT selection and ignoring what happens before and after surgery. In neurosurgery, every phase matters. From patient intake to final payment posting, each step must flow smoothly, or the claim will stall, be denied, or be underpaid.

Let me walk you through how neurosurgery billing actually works in day-to-day practice, the same way experienced RCM teams handle it.

Start With Eligibility and Benefits Verification

Billing begins long before the surgeon enters the operating room. The first and most important step is verifying the patient’s insurance eligibility and benefits. Neurosurgery procedures are expensive, and payers do not make exceptions for missing coverage checks.

Eligibility verification should confirm whether the policy is active on the date of service, whether the neurosurgeon is in-network or out-of-network, and whether the facility is covered. You also need to verify surgical benefits, inpatient versus outpatient coverage, deductible status, coinsurance, and out-of-pocket maximums.

For spine and cranial surgeries, it is critical to confirm whether the plan requires referrals or prior authorizations. Many commercial payers deny neurosurgery claims simply because authorization was not obtained correctly, even when the procedure was medically necessary.

Obtain and Validate Prior Authorization

Most neurosurgery CPT codes require prior authorization, especially spine fusion, cranial tumor resections, and peripheral nerve reconstructions. Authorization is not a formality. It is a clinical review by the payer.

The authorization request must match what will actually be performed. If the authorization lists a decompression but the surgeon performs a fusion, the claim will be denied even if both procedures were medically necessary.

Diagnosis codes must support the requested CPT codes. Imaging reports, conservative treatment history, and clinical notes should align clearly. Payers are very strict about this alignment.

Once authorization is approved, store the authorization number in the patient record and attach it to the claim at submission. Missing or mismatched authorization numbers are among the most common reasons for denials in neurosurgery billing.

Code Directly From the Operative Report

Neurosurgery coding must always be driven by the operative report, not by the schedule, surgeon preference, or historical billing patterns. The operative note is the legal and billing foundation of the claim.

Coders should review the full report and identify the anatomical level, laterality, approach, pathology, and surgical intent. Every CPT code billed must be supported by language in the note.

For example, if a lumbar decompression was performed at two levels, the operative note must clearly state both levels and the work performed at each. If instrumentation was placed, the report must explain why it was medically necessary and how it was used.

Microscopy, navigation, and neuromonitoring must also be documented precisely. Many neurosurgery CPT codes bundle these services, so separate billing is only allowed when the primary code does not include them.

Experienced billing teams often query surgeons when documentation is unclear. This is not about questioning clinical judgment. It is about protecting revenue and compliance.

Apply Modifiers Carefully and Defensibly

Modifiers are unavoidable in neurosurgery billing, but they are also heavily scrutinized. Every modifier applied should have a clear rationale and supporting documentation.

When multiple procedures are performed in the same session, modifier usage must follow payer rules. Some payers automatically apply numerous procedure reductions, while others expect the billing team to indicate the primary procedure.

Modifier -59 or the X-modifiers are frequently used to bypass bundling edits in spine surgery. These modifiers should only be used when procedures are genuinely distinct. Overuse without documentation invites audits.

Modifier -22 may apply when the procedure required significantly more work than usual, but a detailed operative note must support it, and often a written explanation is required. Without that, reimbursement rarely increases.

Global modifiers such as -24, -25, and -57 should only be used when E/M services meet strict criteria. Improper use during the global period is a common compliance risk in neurosurgery.

Submit Clean Claims With Correct Place of Service

Once coding is complete, the claim must be submitted accurately and in its entirety—place of service matters. Inpatient hospitals, outpatient hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, and office settings each follow different billing rules.

Diagnosis codes should be appropriately sequenced, with the primary diagnosis reflecting the main reason for surgery. Secondary diagnoses should support complexity and medical necessity without overcoding.

Attach authorization numbers, operative dates, and any required modifiers. Missing data elements delay payment even when the claim is otherwise correct.

Most neurosurgery practices that struggle with cash flow are not undercoding. They are submitting incomplete or inconsistent claims.

Monitor Reimbursement and Post Payments Correctly

Payment posting is not just data entry. It is a critical audit function. Each payment should be compared against expected reimbursement based on payer contracts and fee schedules.

Underpayments are common in neurosurgery, especially with commercial plans. If you miss them, they quietly erode revenue month after month.

Medicare payments should align with the Physician Fee Schedule and RVU values. Any deviations should be investigated promptly.

Adjustments, write-offs, and patient responsibility must be posted accurately. Clean books are essential for compliance and financial reporting.

Manage Denials and Appeals Aggressively

Denials are not the end of the process. In neurosurgery billing, they are part of the workflow.

Denials should be categorized by reason, such as authorization issues, coding edits, medical necessity, or documentation deficiencies. Patterns matter. Repeated denials usually point to a process gap.

Appeals must include clinical notes, operative reports, imaging, and payer-specific arguments. Generic appeal letters rarely succeed for neurosurgery claims.

Timely filing limits are strict. Missed deadlines turn appealable denials into permanent losses.

Practices with structured denial management workflows recover significantly more revenue than those that treat denials as isolated events.

Close the Loop With Compliance and Audits

The final step in neurosurgery billing is internal review. Regular audits help identify risks before payers do.

Audit both paid and denied claims: review modifier usage, global period billing, and documentation quality. Provide feedback to surgeons and coders when trends appear.

Compliance is not about fear. It is about sustainability. Neurosurgery practices that stay audit-ready protect both revenue and reputation.

Conclusion

Neurosurgery billing is not something you can afford to get halfway right. The CPT code itself is only one piece of a much bigger puzzle. What really drives payment is how well the procedure is documented, how accurately modifiers are used, and how closely the claim follows each payer’s rules.

Medicare and commercial plans play by different standards. Medicare is predictable but unforgiving when documentation or LCD requirements fall short. Commercial payers often pay more, but only when authorizations, coding, and contracts line up exactly. Treating both the same way is where many practices run into trouble.

The neurosurgery practices that remain financially healthy are those that stay organized and proactive. They verify coverage early, lock down authorizations, code directly from strong operative reports, and review payments rather than assume they were paid correctly. They also audit themselves regularly, so payers don’t do it for them.

At the end of the day, clean neurosurgery billing is about control. When your coding, documentation, and billing workflows are aligned, revenue becomes more predictable, denials slow down, and your team can focus on patient care instead of chasing payments. That’s what sustainable neurosurgery billing really looks like.